What is Ocean Acidification?

The Basics

Scientists estimate that the ocean is 30% more acidic today than it was 300 years ago, traceable to increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) from fossil-fuel combustion and land-use change. As human-generated CO2 is released into the atmosphere, about half of it stays there and much of the rest is absorbed by the ocean. For instance, about a million tons of CO2 will enter the ocean in one hour today. The additional CO2 lowers the pH and increases the acidity of seawater. The current rate of change of ocean acidification (OA) is faster than any time on record (10 times faster than the last major acidification event 55 million years ago). Learn more about the chemistry.

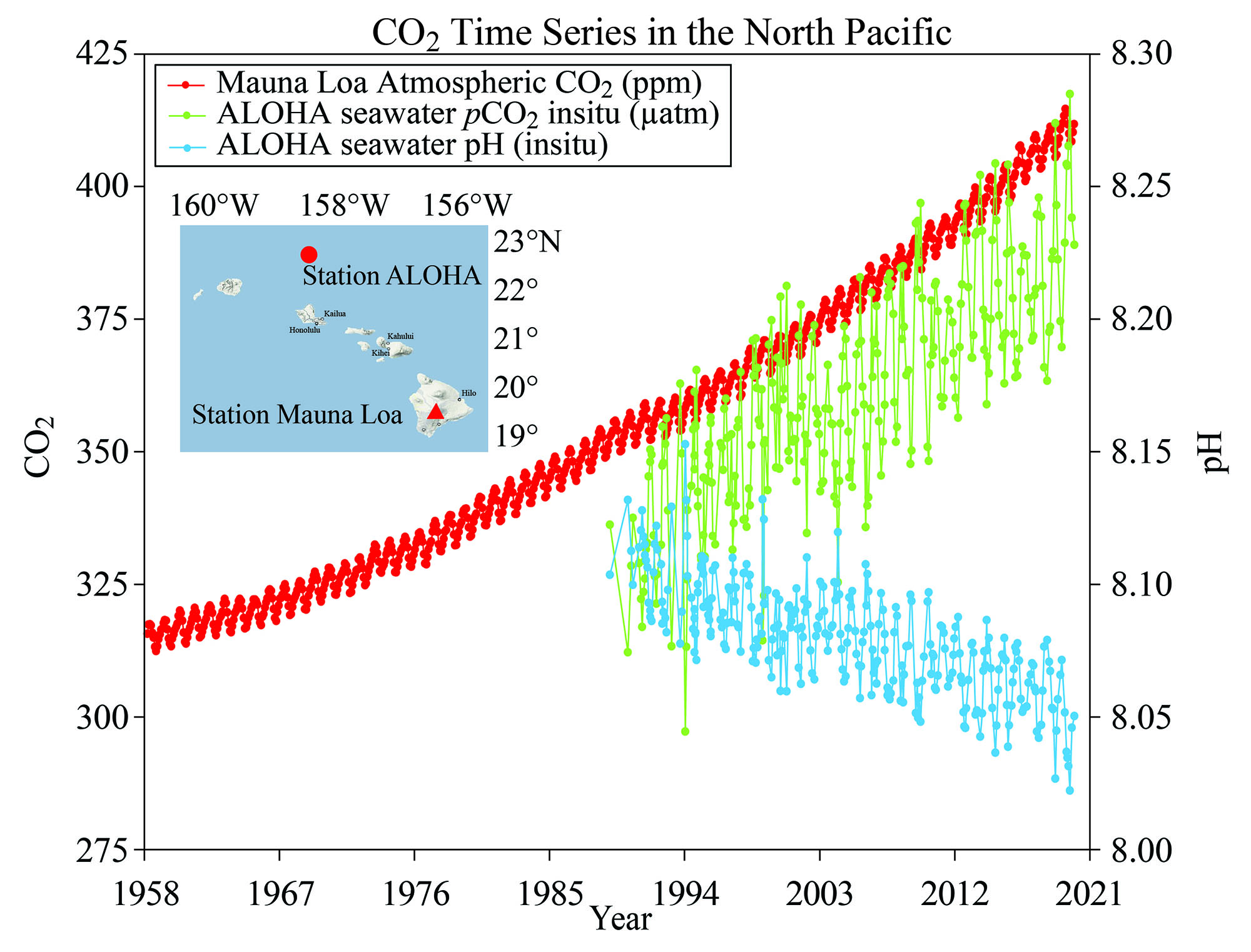

This graph illustrates the correlation between rising levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere at the Mauna Loa observatory off Hawaii with rising CO2 levels in the ocean. As more CO2 accumulates in the ocean, the pH of the ocean decreases. (Courtesy of NOAA/Modified after R.A. Feely, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society)

Implications for Marine Life

Lowering the pH of seawater affects the ability of shell-building organisms to build and maintain their shells. These include crab, oysters, clams, sea urchins, corals, and some kinds of plankton. Pteropods, which are one of the foundational pieces of the marine food chain in Alaska, are expected to be particularly sensitive to OA.

Changes in ocean chemistry can affect the behavior of non-calcifying organisms as well. For instance, the ability for some fish to detect predators is reduced in seawater with higher CO2. When these organisms are at risk, the entire food web may also be at risk.

Why is OA in Alaska a Particular Concern?

Alaska is expected to experience the effects of ocean acidification faster and more seriously than lower latitudes. Waters in Alaska are both ‘cold and old’: cooler water temperatures and global circulation patterns mean that Alaska waters naturally hold more CO2 year round. On top of this high baseline concentration of CO2, other processes also naturally lower the pH of Alaskan waters on a seasonal scale. In some areas, winds and storms can bring even colder and older — and more acidic — waters to the surface, especially in the Beaufort Sea.

In the Bering and Chukchi Seas, large phytoplankton blooms occur every year. These phytoplankton are an important food source for fish and shellfish, but as the phytoplankton blooms die, they sink and release CO2 as they are consumed by bacteria.

Other aspects of climate change are also accelerating the rate that ocean acidification occurs in Alaska. Melting glaciers in the Gulf of Alaska add freshwater that drain directly into the ocean, reducing the number of carbonate ions available for organisms to build their shells and skeletons.

More Resources

As a result of all of these processes, Alaskan waters are already near acidification thresholds with high enough CO2 to threaten marine life. This ecosystem already lives on the edge! So it only takes a very little bit of extra CO2 — like the extra CO2 that humans have put into the atmosphere– to create hazardous conditions. In the Chukchi and Bering Seas, the natural CO2 from the ‘cold and old’ baseline and bacterial respiration of phytoplankton combines with human-generated CO2 to create seasonal ocean acidification events. The Arctic Ocean is even ‘colder and older,’ and adding anthropogenic CO2 is pushing this region into sustained corrosive conditions.

What does this mean for people?

Alaskans are heavily reliant on the ocean for their lives and livelihoods. The seafood industry in Alaska has an estimated value of $5.8 billion and constitutes the largest private sector employer in the state. Almost half the seafood in the U.S. comes from Alaskan waters. Both direct and indirect effects of ocean acidification could have serious implications on the species being harvested, and the food web that sustains these fisheries. Researchers are trying to better understand the chemical and ecological systems at play so we can anticipate and respond to future changes due to ocean acidification.