Brian D’Souza was a NOAA intern aboard the 2022 NOAA Gulf of Alaska ocean acidification research cruise. The cruise departed Seattle in August 2022 with the mission to survey ocean chemistry conditions throughout Southeast Alaska and the eastern Gulf. Brian is currently a junior at University of Illinois.

The Rachel Carson, operated by the University of Washington as part of the UNOLS fleet.

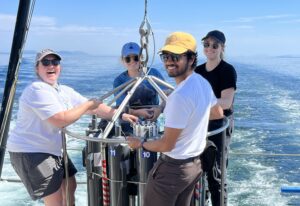

It took me an absurd two weeks to sit down and properly reflect on my time at sea aboard the Rachel Carson, a testament to my newfound course load and my trepidation about sorting through the thousands of photos from our voyage. I am a Geophysics and English student. Keen readers may notice that neither of these majors is Marine Biology or Ocean Chemistry, the fields our ocean acidification research inhabits. I was used to working in areas beyond my studies. I spent my summer internship at PMEL doing hurricane mapping, and I have enjoyed cultivating a fairly varied research background at school. Still, the prospect of going to sea and doing research first-hand was a dramatic departure even for me. I had no idea what to expect, and I knew even less about the science I would be facilitating. I had been told we would be conducting CTD sampling, an acronym I was utterly unfamiliar with that stood for Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth. In a brief meeting with our Chief Scientist, Dr. Jessica Cross, I was informed that the actual process of taking samples mostly amounted to opening, filling, and closing assorted bottles.

“Have you tapped a keg before?” Dr. Cross had asked over Zoom. “It’s just like that.”

“Yeah, I have,” I lied. Bad enough that I was inexperienced, I couldn’t risk looking uncool too.

Jess teaching the group about CTD Niskin procedures (Brian in yellow hat).

Still, despite my apprehension, I was excited to be on the team. I knew I needed to spend time at sea before I applied to the NOAA Corps in the fall. Part of this necessity was tied to resume building, but more importantly, if I ended up hating life at sea, I needed to find out now. The days leading up to departure were a mad scramble as I ran around the city assembling a collection of rain boots (several sizes too small), assorted jackets (I wore one the entire time), and work gloves (used once). On Monday, August 8th I came aboard, met the crew, and we departed Seattle. I enjoyed beautiful views, clean air, and some of the best ribs I’ve eaten that night as we began our way up the inside passage.

We continued on this route for a few days, traveling through calm straits past foothills and forests. I immediately saw the appeal of life on a ship. It felt like one long, continuous road trip aboard, without the cramped legs and gas station food. We learned about the instruments and procedures we’d be using, I slowly gained a working understanding of the task ahead, and I surmised that tapping a keg wasn’t particularly difficult.

Finally, I had my first shift as we entered the Gulf of Alaska. I had been feeling great the previous days in the inner passage, and I assumed that I had circumvented seasickness. I believe I puked five times during that first shift, before being graciously allowed to head to bed early. By the next day, I had gotten my sea legs, and I immediately disregarded the Bonine I had stocked up on. Over the next few days I settled into a rhythm as my sleep schedule adjusted, the work turned more routine, and the water became more familiar. I read papers about ocean chemistry and learned about how acidification affected Alaskan crustacean populations and thereby the fishing industry. I was certainly still no expert, but I understood much more about the research mission. The lifestyle that had seemed so alien beforehand turned comfortable far faster than I expected.

After a week or so of taking casts, we spent a couple days in port at Sitka to avoid inclement weather. It was perhaps the most beautiful town I have ever seen, like the best parts of five different national parks combined around one (relatively) tiny fishing town. Our entire crew went out to eat that night, and I had a great time. The Carson’s crew is a collection of some of the most interesting adults I have ever met. I wish I had spent more time listening to their stories, and less time sleeping.

The science team in front of the John Hopkins glacier, complete with props.

Eventually, we departed Sitka and reached the highlight of the trip: Glacier Bay. I hadn’t even known that the National Park existed beforehand, and yet it is by far the most spectacular one I have been to. Alaska as a whole is filled with a cold, vast beauty that surpasses everything else. Nowhere else has hit me with the sheer scale that Alaska did, but Glacier Bay was still a cut above. The massive bay was filled with brilliant green water, which stretched to forested banks before snow-capped peaks. The waters and forests teemed with life as we saw whales, seals, sea lions, puffins, bears, and mountain goats. We saw so many sea otters that it almost became routine. Unfortunately, I had forgotten my DSLR camera, but luckily I had bought a little short throw telescope that I used constantly in the park. I’ve never taken more pictures of anything ever.

Things wound down after we left Glacier Bay, and soon we were back in Sitka, where I would disembark and fly home. After three weeks at sea, the prospect of returning to a school desk somehow seemed daunting. I did not want to leave, but I knew I had learned much from a spectacular experience, and I am immensely grateful for it. Since returning to school I have gotten the opportunity to talk about the cruise with professors and younger students, and I have been surprised by how experienced I feel now. One little research cruise is nothing to a proper marine biologist, but I have done something few undergrads have done at my school. I have proven to myself that I’ll be fine at sea, and I feel comfortable about the career I am pursuing.

The author, “feeling confident about my career aspirations, sea legs, and jacket choice.”

However, my biggest takeaway, and the message I want to spread to incoming students, is that you do not need to be an expert to make meaningful research contributions. Including this trip, I have conducted research in the fields of marine biology, ocean chemistry, sediment stratification, glaciology, and hurricane mapping. Approximately one of these fields pertains directly to my Geophysics major, and yet I now feel comfortable in all of them. Of course, this jack-of-all-trades approach coincides with my more generalized NOAA Corps ambitions, but I hope other students know that they can just go out and study whatever interests them. You don’t need to understand everything about a field to facilitate its research. Sometimes just being enthusiastic to help is enough.

On a not unrelated note, I have a meeting to declare a biology minor on Thursday.

Results from the 2022 NOAA Gulf of Alaska Ocean Acidification Cruise are currently under analysis. Stay tuned for more on what we learned. This effort was funded by NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program.